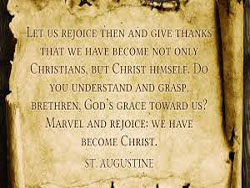

Cellitinnen Augustinian Sisters

Augustian Spirituality

According to Dublin Documnet

Our religious life as brothers and sisters following Augustine’s Rule has similarities with other religious and yet has its own proper traits.

What are the characteristic basic ideas of our Augustinian spirituality? Or, What is the common spiritual heritage that St. Augustine has handed on to us as our legacy? The well-known “Dublin document” speaks of three chief themes of Augustinian spirituality which are meaningful for our time: These are, firstly the search for God, secondly, community with Christ, and thirdly, all-embracing love.

I. The search for God

A longing for a deeper meaning to life, a kind of homesickness for God is interwoven with our lives. Ever more people are weary of a society whose egoism, secularism and blind faith in progress do not know how to answer the ultimate, pressing questions of mankind. Here too is verified the saying of Augustine: “You have made us for yourself O God. On that account our heart is restless until it rest in you.” (Conf. 1,11). Only when a person enquires about God, seeks him and goes towards him does he find meaning and fulfillment for his life. As spiritual sons and daughters of St. Augustine, we are road signs and witnesses, both individually and as a community, to our fellow men in their search for God and for meaning to their lives. It is for us today an important and timely apostolate. Of course it is a task to which our religious communities can accomplish only if the individual members are every day concerned honestly and openly with their personal union with God. We all, however, experience how often enough we fail in this aspect in the mad rush and superficiality of our century.

Were we today to have with us St. Augustine and able to ask him: Tell us now what before all else we need today for the renewal of our religious life? — I believe he would make this point: A religious is a person who has determined to seek God and God’s kingdom in everything. This is why he reminds us in the Rule: “You lift up your heart and do not seek earthly vanity” (1,7).

Augustine prefers to designate religious as “servants of God” or as “slaves and handmaids of God” who have put themselves entirely and individually at the service of God. In this designation as “slaves and handmaids of God” is expressed the unconditional nature of our self-gift to God. God should be at the very centre of our lives. In this regard Augustine speaks of a “free service in God’s presence which we exercise in the cloister.” (Epist. 126,7). We exercise this service to God not because we are compelled to it, but in the freedom of God’s children, a service full of availability and love.

To seek God above all and in all is for Augustine our daily task. This means seeking him in daily prayer and in the community Eucharist, in the service of one’s fellowmen and one’s brothers and sisters, in the hours of work and recreation, in quiet as well as in constant openness to his holy will. Augustine prayed once: “Let me not grow tired of seeking you.” (De Trin. XV, 28, 51). Is this not the special need of many people at present, even amongst Christians? They have become tired of seeking God. They have forgotten Him, He is of no more interest to them, they live and leave Him aside. Augustine, in a sermon, compares such a person with a traveller on the way home. On his way, however, in one of the primitive inns of that time, he finds in the place jug and bowl in which food and drink is given him, such joy that he sets his heart on it and wishes to go no further, and forgets his beloved at home who full of longing awaits his return. To such foolish people Augustine likens a Christian who sets his heart on earthly things and so forgets God and the meaning of his life. For us religious not to become weary of seeking God is even itself a timely apostolate, an important spiritual service which we owe our fellowmen.

II. Genuine community life.

The special following of Christ which religious live out is exemplified in the New Testament group of disciples whom Jesus gathered around him. These men from whom He later chose His twelve apostles, were called by Him into a closer community. Precisely through community lived with the Lord they were to offer first hand witness to God’s kingdom. Jesus thus expressly committed them in his farewell address: “A new commandment I give you for one another! As I have loved you, so ought you love one another. From this will all people know that you are my disciples; if you have love one for another.” (Jn 13, 24). Jesus wished to tell them in this way: It is precisely your unity and harmony, your love for one another shall convince the people who do not know of the truth of my teaching. You, through your community and love for one another, should be a sign of me for them.

For Augustine this is even the meaning and task of religious life. So at the beginning of his Rule he puts the sentence: “The first purpose of your community life is to live harmoniously together with one heart and one soul on your way to God.” (Rule 1,3). In this brief sentence Augustine uses the word “one - unus” no less than four times. He literally wants to tell us how much he is concerned that we really form a unity of heart that is God directed amongst us. The sentence contains the program for Augustinian religious life. For Augustine it has to do with the foundations of a community altogether rooted in God, in which all are linked together in a whole that is full of life. Augustine is, however, aware that a true community life can only come about where people relate to one another. The concept of community is the angle from which Augustine treats and builds up the whole religious life.

Community living in the monastery according to the Rule is not based on mere natural good will. The community has its roots immediately in God. Christ and his Holy Spirit are the soul and life principle of the community. We experience ever and anew the nearness of the Lord through the love of our brothers and sisters. Above all, in the celebration of the Eucharist is fulfilled in us His promise: “Where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I in the midst of them.” (Mt. 18,20).

There is no doubt but that the Augustinian community ideal is for our time especially pertinent. For in the technical society of this century people have an urgent need for human contact, for friendship and genuine brotherhood. There exists today, and not only amongst old people, so much isolation and loneliness. For this reason are we called to give witness through our genuine Augustinian community living, that Christ’s teaching possesses the power to lead men out of loneliness and egoism.

It has been said: For Augustinian brothers and sisters “community living is the first apostolate.” This of course does not in any way weaken the significance of involvement in apostolic and charitable service of one’s neighbour.

To clarify this we must search for the real roots of this service to one’s fellowman. Our involvement separates us from the foundation that bears us along firmly if we are not connected with the inner roots of religious life, if we fail to contribute always in a decisive way to our belonging to a living community, if each day at the Eucharist, at the table, at recreation and work we do not give living expression to our love for those who have been given to us as neighbours in our convent by God.

As religious according to the mind of St. Augustine we are above all brothers among brothers, sisters among sisters. Young people of our time will find our religious life attractive to the extent that they experience with us a genuine humanised Christian community. Precisely as communities are our houses in these times a true witness to Christ and his kingdom, and a sign of hope in that God gives us people the power to overcome self-seeking and to grow ever more in the love of Christ.

III. All-embracing love

Christian art has portrayed Augustine holding a flaming heart as an expression of his. Precisely from us religious God and the world are awaiting a credible witness to love, an all-embracing love, for God and for people.

A religious is above all, for Augustine, a loving person, that is, one whose love is determined by the love of Christ. Of this Paul says in his high song of love (1 Cor. 13,8) “Love never gives up.” It is precisely on this that Augustine makes us think when he says in the Rule: “Above all the vicissitudes of earthly concerns let love shine, which remains for ever.” (Rule V, 31). Even people who do not have much time for the Church today, allow themselves to be impressed by a Christian who lives from love. Think of the high respect which is shown all over the world for Mother Teresa of Calcutta.

What does Augustine really mean by the virtue of Christian love? He means a love that embraces all: God and one’s neighbour, Christ the Head and His Body the Church and all its members. Augustine places no sharp boundaries between love of God and neighbour. Wherefore he once wrote: “Whoever loves his neighbour truly, what else does he love in him other than God?” (In Jn. Evang. 65, 2). Love of God and neighbour does not allow itself to be split in two, Augustine often stresses. It follows for him that when we deny love to others, e.g. we won’t accept them or close ourselves to their need, we meet them with disdain or even with hatred, then we are denying love to God Himself.

Charity is then for Augustine the characteristic sign of a religious. He writes: “The person who possesses love is born from God. The ones who don’t have it are not from God.” “Without it whatever you have is useless. Love alone suffices, even if you possess nothing else.” (In Jn. Ep. 5, 7). To grow in this love is the real purpose of a Christian life: Love beginning, says Augustine is perfection beginning, love growing is perfection growing, perfect love is complete perfection (De nat. et grat. 70, 84). The basis for this Augustine finds in the words of the Apostle: “God is love” (1 Jn. 4, 8)..

Augustine understands Christian love as serving love. Christ Himself lived out this for us: “I am in your midst as one who serves.” (Lk. 22,27). Let us think of the washing the feet which Christ performed for his apostles at the Last Supper. Our specific vocation is to follow the Saviour on this way of love as service. Augustine is convinced that in such selfless readiness to serve others the true love of religious is manifested.

We live at a time when not unusually a crass striving for possession and an egotistical will dominate human life, and so many are all out to grab as much as possible for themselves. For Christians and religious, love must win out precisely in these situations. “Love does not seek its own advantage” (1 Cor. 13,5). Augustine quoted these words of the Apostle in the Rule. It should define our personal attitude and that of our religious community to goods and chattels.

Augustine also saw an immediate contradiction to Christian love in all thinking and striving after power. This temptation exists not only for those who occupy positions of government but also for those who are in positions of service. Jesus laid down in this regard: “Whoever among you would be great, must be your servant, and whoever would be first, must be your slave” (Mk. 18,4,31). The loving service of one’s fellowman is thus the characteristic sign of a Christian. Augustine also expects from us what he wrote in the Rule: “that we serve others without murmuring,” i.e. in love (Rule, V, 38).

Augustine understands this virtue of love as a sharing in the inconceivable love of God Himself. Again and again he quotes Rom. 5:5: “The love of God has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us.” So it is the Holy Spirit who should ever more strengthen us in the love of God and fellowman. At times we experience difficulties in the practice of Christian love. It becomes somewhat hard for us. The loving sense demanded of us by our calling costs us much trouble and control. This is when we should call on the Holy Spirit for His help, something He can and will give us with His grace. In any case Christian love is the special fruit that our religious life should ever lead to more and more maturity.

This overview of the basic concepts of Augustinian spirituality would be incomplete were we not to acknowledge, in humility, with Augustine that “all is grace.” For it is the work of the grace of God going before us that we bestir ourselves ever again to seek Him, to come nearer to Him and love Him more. It is also the work of grace that we are together in the cloister “with one heart and soul for God.” It is the work of grace when we grow and become strong in the love of God, in undivided love for God and neighbour.

For this reason Augustine reminds us at the end of his Rule: When you establish that you have followed the prescriptions of the Rule, “So thank the Lord, the giver of all good” (Rule VII, 49). Augustine here means: Everything good that we do is, in the last analysis, the work of God in us. We could collaborate with Him but only while he was strengthening us.

Augustine does not wish us, however, to overlook our good works. Only we should not boast of them as if were they all completely our doing. In a sermon he says: “Don’t boast even when you’re good. For in boasting of your good works, you are bad” (In ps. 25, II, 11). Pride ruins just about everything.

In his Confessions Augustine has depicted the erroneous ways of his youth, but also his return home to God. The whole work is a thankful description of how he was freed from guilt and sin through the supreme power of divine grace. Let us hear his words: “I call upon Thee, O my God, my Mercy, who didst create me and didst not forget me when I forgot Thee” (Conf. XIII, 1,1). Augustine did not forget during his whole life how God had overwhelmed him, undeservedly, with grace.

Augustine would also like to lead us to this thankful acknowledgement of the workings of the grace of God in our life. For our life too as Christians and religious is a life under grace. Moreover, what we have is God’s gift, as Augustine says in a sermon: “we are but God’s beggars” (Serm. 61,4,4). I close with the words of the Apostle Paul which St. Augustine so often quotes in his writings and sermons: “What do you then have that you have not received. If then you have received it why do you boast as if you had not received it” (1 Cor. IV, 7).